Charles Anthon as

depicted by one of his students in the end papers of one of his

textbooks.

Charles Anthon as

depicted by one of his students in the end papers of one of his

textbooks.

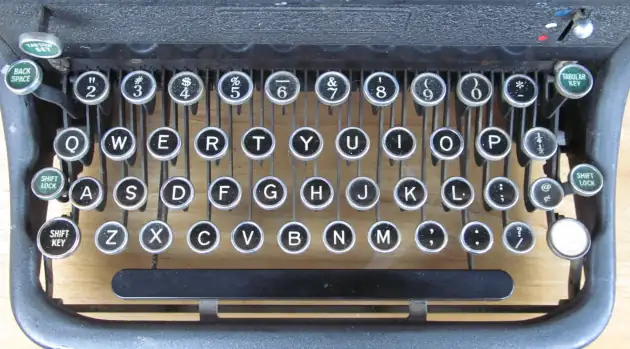

A new page of information about typewriters and how to use them, including the history of typewriters, a number of typing methods from the late nineteenth century to the late twentieth, and some manuals, brochures, and advertisements for various brands.

England’s Arch-Poet Edmund Spenser gets his own page, which includes good scans of the original two volumes of his Faerie Queene and the first collected edition of his works, printed in 1611–1612.

As we continue to revise the classical section of the library, more and more of the best classical authors are being moved to their own pages, with greatly expanded listings. Among them are Cicero, the most famous orator of all time; Sallust, the first great Roman historian; Seneca, the elegant Stoic philosopher and tragedian; Aristotle, the perennially relevant philosopher, scientist, and critic; and Xenophon, the historian and student of Socrates.

Charles Anthon as seen by Mathew Brady.

Charles Anthon as

depicted by one of his students in the end papers of one of his

textbooks.

Charles Anthon as

depicted by one of his students in the end papers of one of his

textbooks.

The first American classicist to develop an international reputation, Charles Anthon finally has his own page.

Professor Anthon had much to do with the high standards of learning in nineteenth-century American universities. Much of Anthon’s work was devoted to bringing the best products of English and German scholarship to America in editions that he improved and expanded. His textbooks on the ancient languages were widely admired, and the proof of their utility may be found in the fact that many professors resented them for making the students’ work too easy. The same was often said of his editions of the classics for students: “The editor…has been charged with overloading the authors, whom he has from time to time edited, with cumbersome commentaries; he has been accused of making the path of classical learning too easy for the student, and of imparting light where the individual should have been allowed to kindle his own torch and to find his own way.” (Preface to Anthon’s edition of Horace.) “His minute and copious annotations at first encountered some opposition,” says his obituary in Harper’s Weekly, “but so little effectual has been the force of prejudice, and so generally acceptable, both at home and abroad, have the Professor’s comments approved themselves that many, even of those who at first were loudest in their denunciations of the system thus introduced, have been compelled, by the positive advantages and rich results of this same system, to adopt as far as possible a similar fulness of annotation in their own publications.”

Professor Anthon’s editions were also usefully expurgated, so that a Victorian schoolmaster could confidently expect nothing shocking or embarrassing to mar the perfect decorum in the classroom. As Anthon wrote in the preface to his edition of Xenophon’s Memorabilia of Socrates, “The great merit of the present text, however, consists in its being an expurgated one. Every passage has either been rejected or essentially modified that in any way conflicted with our better and purer ideas of propriety and decorum, for even in the ethical treatises of the Greeks expressions and allusions will sometimes occur which it is our happier privilege to have been taught unsparingly to condemn.”

Dr. Anthon is also famous in Mormon lore as the Columbia professor who was shown a transcribed “Egyptian” inscription from the Golden Plates and pronounced it a hoax, which has been interpreted in Mormon history as “authenticating” it.

The great classical biographer and essayist Plutarch gets his own page, in which we gather almost five centuries’ worth of English translations, as well as the original texts.

Ovid was translated by some of the great names in English poetry, and now he gets his own page in which the translations are arranged alphabetically by the name of the translator.